Building Effectively using Shape Up

Insights on how to shape, build, and ship great software products from the book 'Shape Up' by Ryan Singer

I want to build great products customers love, but more importantly, I want to have an effective systematic process to bring them to reality.

There are quite a lot of tools, frameworks and methodologies out there on approaching product development systematically. Just a random search would push you to Agile, JTBD, Design Thinking, Lean, Gist among others. Some of these are quite comprehensive and prescriptive, sometimes too much for my liking.

I recently came across Shape Up. It's a collection of practical methods and techniques developed and used internally by 37Signals LLC, a software company, to build and iterate their products. It offers some really interesting insights on how to take raw ideas and shape, build, and ship them.

The book is organised into three areas: Shaping, Betting and Building. Below I’ll keep the same rough structure and pull out insights in each.

Shaping

What exactly is a shaping and why should we care ?

Imagine you run a pottery shop, and you have a team of expert potters. A client comes in and wishes for an elaborate vase to be designed and built. One approach to proceed with this work could be to hand over this unshaped request directly to the potters and let them decide and execute on all aspects of it. While this gives ultimate freedom of expression to the potters to make whatever they think is the right manifestation of the vase, it also shifts all the risks of making the wrong decisions and choices to the potters.

Shape Up argues that a small select group takes up some of the decisions, choices and design work upfront to reduce the risk paths for the potters. For example, a choice could be made upfront on the overall size and weight of the vase, or negative choices like what materials not to use, etc. It's essential that the select group must have deep knowledge and sense of the 'thing/product' to be built, which could be through experience (technical and domain) of building and selling such things before (e.g., senior carvers, business owner).

A well shaped idea has the following properties:

It’s not too detailed and not too vague.

It has to be roughly designed enough to leave space for creativity in the build phase, while not lacking so much detail that the core of the idea is altered during the build phase… its Art!

It is solved and thought through

All rabbit holes, risks, and solution paths have been considered in detail. The feasibility of the idea is thoroughly studied and assessed, with all elements of the solution laid out and analyzed. For example, consider creating an AI app to enhance photos. To shape this idea to be 'solved,' we need to truly understand the limits and behavior of the AI model(s) underneath to have confidence that we are not adding the risk of failure later when we build the app.

It is bounded

Clear boundaries are put in place for what not to do. This can be achieved by placing limits on functionality, the time to build (a certain number of weeks), the choice of technologies, etc. Setting boundaries early on helps reduce the risk of overbuilding or building in the wrong direction altogether.

To achieve the above characteristics, the shaping phase has four steps: Setting Boundaries, Finding the Elements, Addressing Risks and Rabbit Holes, and Writing the Pitch.

Setting Boundaries

Responding to raw ideas; “Interesting. Maybe someday“

Most raw ideas are indeed raw, which means there is no sensible way to give a direct yes or no to them. Saying yes implies commitment, while saying no could mean shutting down a potentially valuable opportunity in the future!

This doesn’t mean shooting down new ideas, nor does it mean getting overly enthusiastic and committing too early. Simply throwing ideas into a backlog for later review is also ineffective, as this is where most ideas are left to stagnate.

A better approach is to give ideas space in people’s minds, allowing them to simmer and resurface when the time is right. Simply put, good ideas tend to find their way back.

Understand the need behind an idea

Many times, raw ideas are an amalgamation of a problem and a solution. Worse still, it might not even address the actual problem but a peripheral one, rendering the proposed solution ineffective. It can be a mess.

There is a need to dig deeper and not accept raw ideas at face value. Ask sharp questions and use various methods, such as the 5 Whys technique, to uncover the core problem that the idea aims to solve.

Assess the appetite for taking action on an Idea

Raw ideas can either excite or challenge us, while some may not evoke much of a reaction at all. However, getting too excited too early can easily lead to a waste of time if we jump into it without thorough consideration. Conversely, we could feel challenged by the difficulty of realising an idea.

Appetite—how much attention and time we are willing to direct towards an idea—is an effective ‘constraint instrument’ that aids in making early shaping decisions.

Shape Up suggests setting the appetite in two sizes: Small and Big. A small batch could involve 2 engineers for 2 weeks, while a big batch could include 2 engineers and 1 designer for 6 weeks. The key insight here is that both options represent fixed blocks of time and resources with variable scope.

These batches form the basic ‘mold’ for any work related to the idea to fit within. This encourages shapers to make choices and trade-offs when selecting and shaping work within these time and resource constraints.

It's important to note that you don’t have to strictly follow to the exact recipe of small or big batches as suggested in Shape Up. Experiment with your own sizes and resource mixes to see what works best.

Finding elements of a solution

With a narrowed-down problem to solve and our appetite constraints in place, the next step is to move into a rough solution definition space. Since there can be a ton of ways to explore a solution space, it’s important to move quickly and cover many solution paths with more breadth than depth.

The right level of abstraction is crucial at this stage. We need to avoid overly detailed solution designs. Detailed wireframes or components too early can lead to getting stuck. It's a good idea to explore solution ideas broadly as much as possible.

Breadboarding is a well-known electronics prototyping technique where the aim is to realize an electronic system in full function without worrying about creating an actual industrial circuit board. The main advantage is the flexibility it offers. Think of finding elements of your solution as if you’re breadboarding a solution. This means identifying components, their interconnections, and the flow of the solution.

Some questions we could use to guide us in this solution definition are:

What are the key components or interactions ?

What are in inputs and outputs ?

Where in the current system does the new thing fit ?

Address risks and rabbit holes

As we shape different solution options, we want to discover and address as many potential risks and unknowns as possible early in the process before a certain solution option gets to the build stage. Finding solution elements is a fast exploratory process, as it should be, but now we want to take a magnifying glass and look critically at each element of the solution and its interactions between elements.

One approach is to 'dry run' the solution with its elements from the user's perspective and ask these questions:

Does this require new technical work we’ve never done before?

Are we making assumptions about how the parts fit together?

Are we assuming a design solution exists that we couldn’t come up with ourselves?

Is there a hard decision we should settle in advance so it doesn’t trip up the team?

At this stage of the shaping process, it's important to bring technical experts up to speed, walk them through the problem & solution. This is a critical feedback loop in the shaping process.

Up to this point, the solution is still wet clay, ready to take inputs from technical experts, which could be in the form of collaborative revisions of the proposed rough solution or a completely different approach to solving the problem. So it could either be a general positive validation of the solution OR a signal to go back to another round of shaping

Write the Pitch

At the end of the shaping phase, we have a clear problem definition, elements of a solution, potential risks considered, and rabbit holes patched. Now it's time to take this shaped work to a betting table in the form of a pitch!

The pitch is the first properly documented version of the idea, to be used to lobby for resources, gather wider feedback, or even serve as an artifact to capture an idea in a coherent form for future consideration.

We’ve de-risked our concept to the point that we’re now confident it’s a good option to give to a dev team.

The pitch has five key ingredients concisely written based on all the work we have done so far:

Problem: The raw idea, a use case, or something we’ve seen that motivates us to work on this.

Appetite: How much time we want to spend and how that constrains the solution.

Solution: The core elements we came up with, presented in a form that’s easy for people to immediately understand.

Rabbit holes: Details about the solution worth calling out to avoid problems.

No-gos: Anything specifically excluded from the concept: functionality or use cases we intentionally aren’t covering to fit the appetite or make the problem tractable.

The pitch is then socialized with stakeholders so that everyone has time to read and comment on the pitch in an asynchronous manner. This could be done using any appropriate tool for asynchronous sharing and feedback, for example, a tracked MS Word document could be one simple approach. The outcome of this stage is a risk-reduced, well-thought-out problem and its solution in the form of a written document that has been reviewed by a select group. Remember, no decision has been made yet to take action on it.

Bet on a pitch

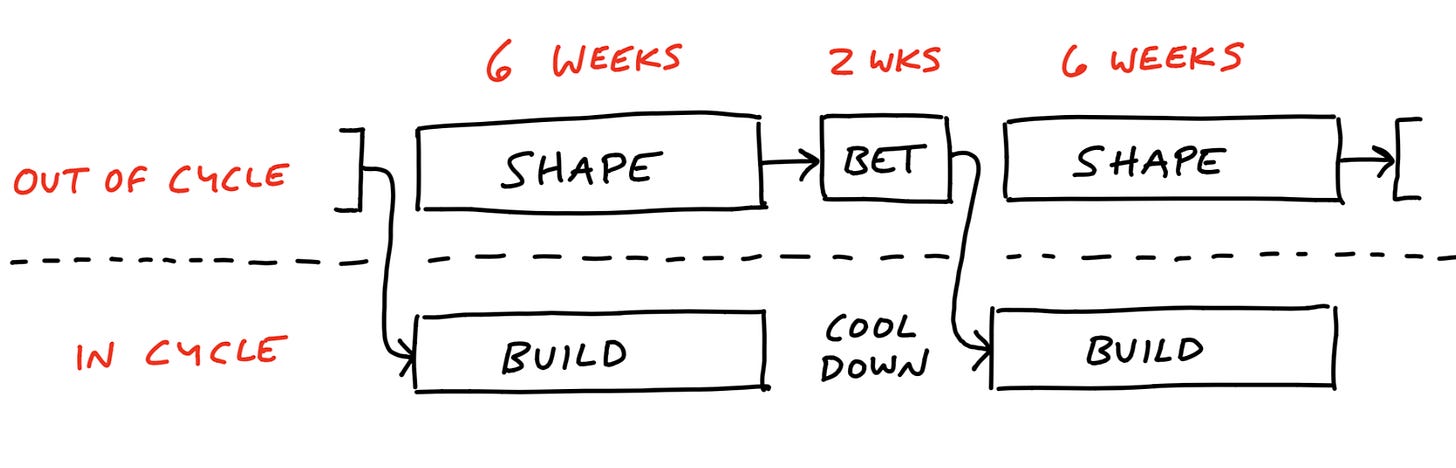

The betting table is a meeting held by a small group of stakeholders in a cool-off cycle (2 weeks) to decide what to do in the next build cycle (6 weeks)

The participants in the meeting are all the people who have decision-making power and accountability for the work carried out. The typical group consists of a combination of key individuals with a sense of What & Why (business/product leads, strategists, and executives) and individuals with a sense/skills of How (senior technical folks such as engineers, scientists, etc.).

The output is a clear cycle plan (what to do and who to schedule). This plan is based on a full view of resource availability and business priorities. There are no stage 2 or further meetings to discuss. The betting table assumes well-shaped work as input and a clear decision on a committed cycle plan as output.

Key questions to ask at the betting table:

Does the problem matter?

Is the appetite right?

Is the solution attractive?

Is this the right time?

Are the right people available?

How to deal with existing product vs new products

The process described so far lends itself very well to adding a feature or making a change to an existing product. Basically, follow the standard shaping process: shape → bet → build and repeat.

But for completely new ideas (new product concepts), there is a different mode of work before we can push it through shape → bet → build. In other words, we don’t even know what we want to ‘shape‘.

This is where R&D cycles are effective in getting to that initial mass to be shaped further. So instead of betting on a well-shaped pitch, we bet on time slots (Spikes).

We do not expect to ship anything at the end of the R&D cycle. Instead of delegating to a build team, the R&D cycle is resourced with senior people with enough technical and business skills to bring this to life in the form of a prototype.

R&D cycles are still decided cycle by cycle basis depending on the progress made and the available resources to spend on pure R&D. If we continue to see progress in the R&D cycles, eventually a point is reached where this new product idea is pushed to production mode following the standard process of shaping, betting, and building.

Building

Let the dev team breakdown the pitch, don’t do their work for them

The pitch holds the conceptual integrity of the work we want to do, and therefore it is supposed to be a guiding light when the build phase begins. The dev team must be given the freedom to take the pitch and extract their own tasks from it.

It is important to note that this freedom is within the boundaries and the shaping that has already been done. We don’t expect teams to invent a solution from scratch.

That's why the shaped work has to have the right level of abstraction; not too concrete that it takes away the freedom and creative work from the dev team, and not too vague that it leads to ineffective solution paths and confusion.

The team needs time to orientate

In the first few days of the cycle the team will orientate itself to the build at hand, figure out where to start. So much doesn’t get finished or deployed and thats absolutely fine!

There are imagined tasks, and then there are discovered tasks

The dev team is given a pitch to build, and it naturally starts off with some imagined tasks. These are things that the team 'thinks' it needs to build. But very soon, as the actual work starts to happen, new tasks are discovered.

These tasks are discovered by doing real work. It is an unavoidable path in the build process. Also, more tasks are likely to be discovered as more time passes, with an eventual plateau later on.

Integrate one full working slice

Feeling progress in the build phase is so underrated. Aim to get to a single integrative experience or outcome that works, instead of multiple open task all planned to be joined together in the 11th hour to produce an outcome.

This idea is not novel. similar notions are found in Agile methodology and other development frameworks.

Map every task to a meaningful scope

We talked about discovering tasks while we do the actual work and the notion of integrating these tasks into a single fully working slice. A fully integrated slice is a single scope, and a continuous exercise of collecting and organizing these discovered tasks into these meaningful slices constitutes scope mapping. For example, imagine we are building a note-taking app. A note-saving functionality is one complete scope, as is note-loading/opening functionality.

Scope mapping is an ongoing exercise, with most of the mapping done earlier in the build phase, some indicators of good scope mapping are:

When you go through the list of scopes for a project, you see the whole project, with no functionality or path left unidentified. Think of the scopes as an anatomy of the project, like a human body and its parts and systems.

All the scopes have a verifiable closure or output. This means they can be QA-ed effectively.

They have a strong single identity, which means their use in daily conversations is without any confusion or conflict. (The inverse of this are ‘junk drawers’ or ‘grab-bag’ scopes.)

When new work or a task emerges, it can easily be added to one of the scopes without much confusion.

However, there are always cases where some tasks (a small amount) just don’t fit anywhere. In that case, it's sensible to keep them in a temporary 'holding list', but don't let that list grow beyond a single-digit count!

Keep a cool-off space between build cycles

One of the things that you see in many modern Agile dev shops is a maniacal focus on continuous delivery without any breaks, where shipping continuously week after week and month after month becomes a target metric. This is an unhealthy building rhythm and also ineffective in the long run. It doesn’t leave space between builds for any cooling-off time for ideas to simmer or for space to fix and maintain things. The Shape Up system suggests putting two-week cool-off periods between six-week build cycles.

Track and show progress

Estimates serve as one way to set an expectation for reporting progress. If one task is estimated to take 2 days but ends up taking 6, then this shows a lack of progress on this task. Unless the team works like an assembly line with the same work again and again, the estimates are likely to be off.

Asking the dev team to add some uncertainty number to their estimates is another way to manage expectations, e.g., approximately 5 days estimated with an uncertainty of 1 day. But if we track progress against this sort of estimate, it still doesn’t reveal much if there is a delay.

One alternative offered in Shape Up is to add two phases to the task progress status, i.e., ‘Figuring it out’ and ‘Getting it done’. This is visualized with a ‘Hill chart’ graphic (see below)

Even if the actual visualization of a hill chart is not used, just thinking of a task to have these two phases, where most of the time and effort is likely to be taken in the ‘figuring it out‘ phase rather than the ‘getting it done‘ phase, allows the dev team to show progress more meaningfully.

Additionally, this way of progress tracking can be extended from tasks to scopes (each scope can have multiple tasks). A side effect advantage of this approach is that if the scope or a task is stuck at the uphill side ('figuring it out‘), then the senior team members or managers can step in to help understand if the scope needs to be broken down or bring further help to the team, essentially catching uncertainty and risk much faster.

Figure out the most important scopes with the most unknowns first

Some scopes require more 'figuring it out' effort than 'getting it done' effort. In this case, practical advice is to tackle the scopes with the most figuring needed uphill first, and then consider the simpler scopes that only require a set amount of time to get in place. This reduces the risk of delays in the later part of the build cycle.

The scope for change in software or any system is infinite; let constraints and boundaries motivate people to make trade-offs

Software systems offer a massive amount of flexibility in what they could eventually become (functionally, operationally, visually, structurally). Contrast that to a physical system like a building, where you are dealing with a lot more strong non-negotiables like laws of physics and building codes.

It is, therefore, very difficult to nail down (in high definition) the scope of a project or system from the start. Scope creep will definitely happen. Even if we lock the 'requirements' from the business or client and shape these up sensibly, the development team is bound to have new ideas within the detail of the system while they work on it.

Time constraint—the 6-week cycle—serves as a primary way to cut or 'hammer' the scope. Constraints and boundaries enable the team to make decisions and choices, which constitute the scope hammering act.

Identifying must-have and nice-to-have features or elements of the solution is one way to help with scope hammering. For example, backend unit testing could be a must-have, whereas font choice for a note-taking app might be a nice-to-have in V 1.0.

Build with quality, use QA only for the edges

The dev team is responsible for maintaining the quality of work and should ensure testing the build against the standards (testing regime, code reviews, etc.). A separate QA role is for hunting edge cases outside core functionality and discovering nice-to-have tasks, which could then be triaged by the development team for further action.

It's also important not to make QA a gate that all work must go through. It's great to have a QA stage, but it's not a necessary step to ship quality outcomes for customers.

Finally: Is Shape Up a good method to adopt for my team and organisation?

The Shape Up method offers a lot of practical insights toward effectively shaping and building a software system. Although the method presented is quite tightly interwoven, the insights can be taken and adopted in a piecewise, independent manner. See Appendix 3 in the book for further advice on different options to implement this method in your team or company.

Bottom line: There is no perfect method out there. Organization size, culture, nature of business, depth & breadth of skills in the team, all have an effect on how well a method like this can be applied. So, it's best to observe, orient, decide, and act (OODA).